|

Wayne Lineberry

Throwback Pirate

Finally Coming Home

Wayne Lineberry, a Buc with a story to tell, looks to

parlay his financial skills into a future for his Pirates

By

Ron Cherubini

©2005 Bonesville.net

|

Pirates defensive stalwart Lineberry in his

senior

year (1968) press shot (Submitted) |

Giving back has always been part of Wayne

Lineberry’s long-term plans. As a star linebacker for legendary coach

Clarence Stasavich, Lineberry only knew of one way to be a Pirate. That

way was full on, 100 percent. He did it as a player; he’s been doing it

as a fan and Pirate Club supporter. But now, as when he was a player,

he is bringing the sum of his skills – on point – to focus on helping

his beloved Pirates in a way that will ensure that his alma mater has

the tools to keep fighting… climbing… and working its way to the college

football promised land.

Lineberry’s plan has always been to find his way

back to Greenville… back to where he has always felt at home. Only, he

wanted to come back and make an impact on the program. His years as an

executive in the insurance business – first with New York Life and

currently with Virginia Asset Management – have taught him a great deal

about financing futures. And if there is one future in particular he would like to

insure and ensure, it would be that of the program.

“I’ve been trying to get back to Greenville for a

long time now,” Lineberry said from his home in Troutville, VA. “I have

been in the insurance investment business since 1973… most was as a

General Manager of New York Life… living all over the country. One of the

things about getting back to Greenville, in 1983, I moved from

Williamsburg, VA, to Tucson, AZ, with New York Life and I was the GM out

there. The University of Arizona had what was called the President’s

Club. It was an insurance endowment program which basically worked like,

if you bought a $100,000 policy with a $10,000 cash value in 10 years,

it would be like the equivalent of, say, a Purple Pirate (level in the

Pirates Club). I actually hired some football players out there to work

that market. And it is the same now with Virginia Asset Management and

Pirates Club members who are getting involved.

“Dennis Young and I were teammates – we came in as

freshman together – and I’ve talked to Dennis for years and years (about

starting a similar endowment mechanism) and they

finally approved it with the Pirates Club Board of Directors. The reason

I am doing it and trying to get to Greenville and open up an office — it

kind of ties the whole thing in — is that the University of North Carolina

started doing that in the 1960s and they have a $118 million endowment

and we have a $7 million endowment. Small contributions annually today

will leave huge benefits tomorrow. With us not getting in the BCS and

having access to BCS or ACC money, you know, if I can put a couple of

hundred

million dollars in the bank with other agents, it encapsulates what I

can do for my school. For the survivability of the athletics… that is

where I am coming from on that. Hey, none of us are getting out of here

alive and you can’t take too many of your toys with you. We are all kind

of remembered by what you give back. Right now, I am just going to set

up a sales office. As I go off into the sunset… I’ve been fighting for

the university for 40 years and this is my last big fight.”

It should be no surprise that Lineberry is looking

to contribute big-time to the program. It is the only way the former

standout from Wadesboro knows how to play. He is a throwback player

and he doesn’t hesitate to give a little nod the way of his former high

school coach in appreciation for helping mold a Pirates star of the

1960s and, even more so, for contributing to the man he became after

football... though, Lineberry admits, it was never a dull moment

growing in Wadesboro and playing for the cantankerous former Pirates

skipper.

“Growing up in Wadesboro… hmmm,” Lineberry pondered.

“I’ve always been involved in athletics but the big turning point for me

was in 1963. You know, Wadesboro played in probably the toughest 3-A

conference in the state with Rockingham, Hamlet, Sanford and those

schools. We were just a little old tiny school (playing those teams). In

1963, we were

Ed Emory’s first head coaching job and I can unequivocally

say that the season of ‘63 and ‘64 – my junior and senior years – were

unbelievable. I mean, the hardest I ever got hit in high school football

was at half time…and I am dead serious about that.

“Of course, we were like third in the state, we had

a real good team and a couple of us went on to play college, but I mean

Ed is… he’d kick the door in at half time and pick on the stars. He’d

slam me through the locker and just beat the fool out of us. I can tell

you, you know, you ever see The Junction Boys? I watch that

and I just cringe because that kind of reminds me of the way it was (at

Wadesboro High).”

Though it may sound a little rough, for Lineberry

and his ilk, that was the only type of football there was and Emory

exemplified it in every inch of his being. As a player – one that would

garner Prep All-America status under Emory – the fiery coach was just

the igniter he needed.

“Well… here’s one story on Ed,” Lineberry shared.

“Here is an example… the thing I used to hate to hear him say was, 'Turn

the lights on,' or, ‘One more play.’ We’d be scrimmaging but all we did

was hit. We were mean as hell, too, but all we did was hit, hit, hit.

Thursday night before a Friday game he’d cut the lights on and we’d stay

out there for hours and hours scrimmaging. But we had a real good team… a

hard-nosed team, and Battle Wall – both Battle and I were all-state from

little old Wadesboro – Battle went on and signed with Carolina and did a

tremendous job there. But we were playing one of those Rockingham teams

and Battle got this guy in what we called a Twirly Bird… well, it

was 1964, anyway… and you’d catch the running back and instead of

throwing him down, you just start to twirl him around like a top waiting

for the other guys to get to him. So, since he is coming around… you came

in with helmets those days. You know, you can put out a lot people like

that.

“Anyway, Battle got this guy in a Twirly Bird

and the guy slipped out of his grasp and ran for like 40 yards and a

touchdown. Well, Ed Emory goes berserk. The big man goes berserk and

you gotta understand he’s about 275 pounds of testosterone in those

days. So he calls a timeout and I was the middle linebacker because we

ran a 6-1 defense like we did at East Carolina. Anyway, you know Ed has

a speech impediment and so he says to me, ‘Lineberry… Lineberry… come

here.’ So I go over to the sideline and he just jacks me up and knocks

the hell out of me right there on the sideline and he’s beating me up

and my mother is in the stands yelling, ‘Hit him harder.’ That was a

tough crew we had out there. So he threw me back out there on the field

and he said, ‘Semiwall…,’ which is s-e-m-i-w-a-l-l, which was actually,

“Send me Wall.” Now, I’m not making fun of Ed, I can just mock him real

good. I go back out there and I am facing the huddle and I say, ‘Battle,

the big man wants to see you.’ And Battle looks out of the huddle and Ed

says, ‘Wall, Wall… come here, Wall.’ Battle says, ‘Naw, hell no, I’m not

going over there.’ And Battle stayed on the field… I mean, punts,

kickoffs, we’d have 12, 13 men on the field, it was chaotic. Battle

didn’t leave the field because Ed couldn’t run on the field. After the

game, Battle runs straight up to the field house, drops his helmet,

grabs his clothes and he’s got his uniform on. He had a Ford Fairlane

convertible and he ran over to his car, didn’t open the door, jumps and

lands in the seat. He cranks up the car and takes off. Now that is the

way we did things under Ed Emory.”

Bigger, Stronger, Faster

There was never denying that Lineberry was an

athlete. He was always pretty much bigger and stronger than than the

rest of the pack,

so football was a natural fit. In a town where kids dreamed of the day

they would lace them up for Wadesboro High, Lineberry was one of those

kids the coaches took notice of early.

“I was pretty much always bigger than (my peers),”

Lineberry said. “I was probably, like, I was listed at about 200 pounds.

My junior and senior year, I wrestled and went to the state both years

and I went at like 185 my junior year and heavyweight – 197 – my senior

year.

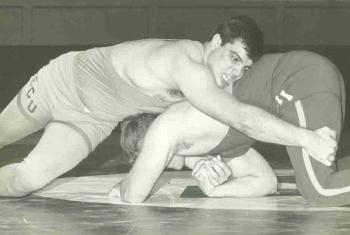

Lineberry shows off his

wrestling prowess for the Pirates

during a

heavyweight match in 1967. (Submitted)

“At Wadesboro, if you were on the football team

back in those days, you either ran track or wrestled or you didn’t play

football. I’ve always been in athletics. I played Gene Smith Wade

Rookies (youth football) when I was six years old and I don’t think we lost three games

from the time I was 6 to 13, so, I’ve always been involved in

athletics.”

Still, for all his natural abilities – and there

were plenty – Lineberry shudders to think what would have happened had

Emory not found his way to Wadesboro.

“If Ed hadn’t of come to Wadesboro, I’d probably

have wound up working in the mills like my parents did,” he said. “Ed

came in and gave me the boost I needed. And it was Ed Emory and the

coaches and Leo Jenkins that got me into East Carolina. He (Emory) was like a

breath of fresh air coming to a small town. He was something we’d never

seen before. Everything he did was first class. You know, he did

everything right by his football team. He was a second father to all of

us.”

Under Emory’s mentorship, Lineberry parlayed his

talents into post-season honors (1st-team all-state and 3rd-team prep All-America)

and a host of scholarship offers, but there had a

been a tug from East Carolina all along the way.

“I thought I’d get a scholarship somewhere,” he

said. “I had scholarships anywhere I wanted to go. Honestly, Battle and I

were both highly recruited. When I played in the all-star game in the

summer before I reported in 1965, they had me listed (as committed) at an

ACC school. I was offered a full scholarship to Clemson by my third game

my senior year. But Ed had brought the whole team to East Carolina for

football camp and it was more exposure (to East Carolina). So, I loved

East Carolina and I loved the school. In those days, it was like N.C.

State, Carolina, and Clemson where you wanted to go… and East Carolina.

“I had the high school grades and the courses, but

I horsed around my senior year and the entrance requirements were giving

me a hard time. Right before the East-West game in Greensboro, I was

listed as going to N.C. State, because I signed with them, but I didn’t

want to go there. There were no girls up there. My dad talked me into

(signing with State) instead of North Carolina because he wanted to keep

me out of trouble. The coaches at East Carolina called and said that

with the entrance requirements, that they could get me in. But I was

told that the admissions folks were kind of questioning (my credentials),

and this was in the middle of summer and I was to report in August. I

don’t know exactly what happened but Leo Jenkins reportedly got involved

and cleared the matter up and said, ‘He’s in.’ I’m in school because of

all the coaches, Stas, Leo Jenkins… I’m honored – I’m a Pirate for 40

years – and I’m honored by (Leo’s efforts).”

Finding Football Heaven

For many freshmen coming into a collegiate

program, the time is one marked by a little fear, a little self-doubt, a

little chaos. For Lineberry, his arrival on campus was not the norm for

a youngster getting read to play with the “big boys.”

“My freshman year… well, I thought I was a

kid in a candy store (referring to all of the beautiful girls on

campus),” Lineberry recalled. “We were all in the dorms together… we’d

scrimmage some with the varsity… we knew all those guys. A lot of the

guys starting on the freshman team, a year later they were gone. I think

we had probably 109 freshmen come in (his first year) and there were

maybe eight or nine that were here by my senior year. It was definitely

a cattle call.”

And Lineberry, being the big-time athlete,

saw East Carolina as another type of candy store. He came in ready to

take the town by storm despite being a newbie.

“I looked around at all of the beautiful

women and the downtown bars and I said, ‘There ain’t no way I’m flunking

out of this place,’” he said. “Of course, I almost did in the first

quarter of my freshmen year. It was just a wonderful experience and it

was a wild time. We were kind of wild coming out of high school. It was

an Animal House situation, especially with the older guys, and

some of us fit right in with it (as freshmen).”

Lineberry, however, came

in not only with the attitude of an upper classman, he brought game.

“I don’t want to say I was cocky, but I

guess I was,” he said.

And Lineberry also recognized the talent

around him.

“Jim Flowe was the fullback and he was

another one who had like 39 scholarship offers coming out of high

school,” he said of Flowe, who to this date is still a close friend. “He

was about 238 pounds and ran a 10-flat hundred. We had some good

athletes and Flowe was the fullback, so our junior year, you're coming

into guys like

Don Tyson,

George Wheeler, guys like that.”

Bred to play linebacker, Lineberry found

himself out of place in Stas’s defensive his junior year.

“Stas put me at left tackle and put Flowe

at left defensive end, so we played on that side my junior and senior

year,” he said. “I’d drop back to linebacker sometimes. I remember when

he moved me. Stas came up to me, being his normal, very sarcastic self,

rubbing his pipe against his teeth, and he says to me, ‘Heyyyyy, Liiiinnnneberrrrrry,’ – that was the way he talked – so he says,

‘Liiiinnnneberrrrrry, we can’t haaaave a 240-pound liiiiiinebacker and

200-pound liiiiineman, so you better go in the line.’

|

|

Lineberry,

right, with former Pirate Kevin

Moran at

the bus station following the

1966 game

against Richmond (Submitted) |

|

“I was like, ‘Oh Lord!’ They were trying to

beef up the line and they had myself and Kevin Moran, Tyson, Wheeler,

these guys, so I played my last two years at defensive left tackle

primarily and actually I thought that had blown my chances to go to pro

ball because of it. But actually I still got drafted – my name came up

because they remembered me from my sophomore year – and that is how I

got drafted by the Buffalo Bills (17th round, 417th

overall).”

Still, even in hindsight, Lineberry

acknowledges that the change did not sit well with him.

“I didn’t particularly like having my

position changed but it was their meal books, it’s their program and you

do what they say to do,” he said. “You gotta be coachable. If they say,

‘Play tackle,’ you play tackle. Oh yeah, it (diminished the fun). I

wanted to be the best linebacker to ever play at Wadesboro High School

and when I came here, I wanted to be the best linebacker ever to play at

East Carolina. But, I started all of my years and did what they asked me

to do to the best of my abilities.”

During his time at East Carolina, he

experienced the highs of success and the disappointment of not meeting

expectations, struggling through a 4-5-1 season as a sophomore in 1966,

leading his team to a fantastic 8-2 campaign in ’67 and then leaving on

a disappointing 4-6 senior season.

“To encapsulate that whole era,…” he

pondered. “In 1967, we had a tremendous football team. We had a really

good offensive line with guys like Kevin Moran and Johnny Schwartz and

Butch Colson – who finished fourth or fifth in the nation rushing – at

fullback. But the next year, these guys leave, and our offensive line

well… let’s just say Butch wasn’t as a productive in ’68. He got beat up

pretty bad then. It tickles me because, I was talking about how the

coaches today… like JT (former ECU coach John Thompson), and I saw where he was talking

about Chris Moore, saying that 75 reps was too many and all that stuff.

And I just laughed like hell. In ’66, we played the University of

Southern Mississippi for the first time ever in Ficklen and we were in

the game and it was like 12-7 into the fourth quarter. My senior year,

they just annihilated us down there. Well, we went the whole Southern

Miss game and did not pick up a single first down. How many reps did the

defense play when we were on the field the whole game? The next game was

the University of Richmond in Ficklen and we had gone into halftime and

still had not picked up a first down. We went six straight quarters and

the defense was playing the whole game… forget (the talk about too many)

reps.

|

|

Lineberry

(56) chases down a Louisville ball

carrier in 1966 (Submitted) |

|

“We beat Richmond my sophomore and junior

years, just like we beat Louisville down here. I told JT, look we were

beating Louisville here in the ’60s. We went a whole game and a half

without earning a first down. Now that’s earning your meal books and

scholarship when you do that.”

Lineberry recalls his time with great

pride. Not just because of his contributions but maybe even more so

because he knows he played during an era of football that has since

disappeared.

“The thing about that era…,” he thought

aloud. “Just like the Junction Boys and Wadesboro High

School, these were tough times, we didn’t get water breaks like they

normally do. I remember we would scrimmage for hours without a water

break. I remember there was this one guy who was a backup center – he

really wasn’t a college ballplayer – but he just loved it and wanted to

be on the team (at ECU). He had one of those old facemasks – a double

bar that just kind of hung down. And we get out there and I started to

say, George Wheeler was real bad about it… but rest his soul, he is not

here to defend himself, but we get out there and somebody said, ‘OK

let’s do it.” We’d break his nose so that he’d bleed on the ball and the

coaches had to come out and change the ball and they’d give us a water

break.

“That was some tough days back then. It

drives me crazy… I wouldn’t know how to tackle if I couldn’t use my

helmet and come in like a battering ram. The one thing that I told JT

when I first met him and this is the God’s honest truth, back in the

’60s, even Ed’s teams, East Carolina was known as a hitting football team

– tremendous contact – and I’ve always said a good hit is better than

sex and twice as long. Doug Buffone, who was a great linebacker for

Louisville in the ’60s and was an outside linebacker in the Dick Butkus

days in Chicago, was talking to about 1,000 people at a coaching clinic

and somebody asked, ‘Doug, what was the most physical game you ever

played in?’ They were probably thinking about Green Bay in the snow or

the Detroit Lions and he was up at the podium and he said, ‘Gentlemen, I

gotta be honest with you. When I was in college, we played this team

called East Carolina. I’ve never been hit so many different ways in my

life and hard, too.’ That’s the kind of reputation we had at East

Carolina back then.”

And Lineberry has a good example of that

from his days.

“In 1967, we played Southern Illinois down

here, and it was all clean football but they left like nine (players) at

Pitt Memorial Hospital when they flew out,” he said. “And so then you

see that and then you see it slack off. Now… I go to most of the games

(at ECU) and I know in the ’90s it slacked off. I just go nuts when (the

players) are not hitting somebody. But going back to JT, I said, ‘You

know, we’ll back you and we want you to win every game but we know that

is not possible, I said, as long as your boys are hitting, that’s East

Carolina football.’ At least that is the way it used to be.”

Lineberry knows that what he is seeing today

on the field doesn’t resemble his days in the Purple & Gold.

“It’s a different game now… it’s just stand

up and push,” he said. “I will tell you this, when I was in

graduate school we had an alumni game, and then in 1975 when

Pat Dye was

here, we had a 2nd alumni game and I came down. I was the

second oldest guy to come down and play – my last season was ’69-’70

when I played a little pro ball, so I hadn’t played in five years and I

got out there. Robert Ellis was the oldest guy there, by the way, and he

was running back the kickoffs – so us crazy old guys showed up. But, I

was back in my linebacker position and one of the guys – a little wide

receiver – did a little down and in. He came across the middle, so I

planted my foot and clotheslined him. I mean, just right knocked his

helmet off. The ball went up in the air and everything else. Now I won’t

tell you what he was calling me, you know. That was 1976 and I clotheslined him and I said, ‘No, you don’t understand, I’m not dirty, I’m a

fossilized old throwback ’60’s linebacker, but come back across my middle

(and that’s what you get).’ Now that was two different eras back then

(compared to today).”

Lineberry’s time at East Carolina was a

tumultuous time for a teen-ager. It was the early stages of the Vietnam

War and even on the tiny campus in Greenville – sandwiched between Camp LeJeune to the Southeast and Fort Bragg to the Southwest – tensions were

in the air. For Lineberry – whose brother had just returned from his

first combat tour at the time – there was quite a bit of emotion running

just below the surface. And when that angst came out, it almost ended

his career.

“I almost got kicked off the team in 1966

because I was over at the Student Union one day with Richard “Rooster”

Narrow – who always reminds me of this story when we talk – but that

was the first year that my brother, Jerry, was in Vietnam with the 5th

Recon in the Marine Corps,” Lineberry said. “I’ve always been a little

conservative... well, real conservative. So, I’m walking in the Student

Union and the art department had a pro Viet-Cong table set up. Now, 1966

was a little early for that stuff to be happening, so we go in there and

stand by the fountain to get a drink. I made a comment to a bunch of

ballplayers and I said, ‘If somebody buys a drink, I’ll go and throw it

on (the guy at the table).’ So they gave me a huge drink, the biggest

you could buy, and I walked up there and said, ‘What are you guys doing

here?’ and I just slung the drink over there. Well this guy jumped up

and he looked like Grizzly Adams in coveralls. I mean, this guy was

bigger than me. When he jumped up, I just grabbed the table and turned

it up and slammed him. I didn’t want to let that big guy up so I was

just pounding away. And we had a melee there and I don’t know where all

the reporters and police came from, so I just slipped away.

“Now, this was right before practice so I

go on over to the field and they say, ‘Coach Stas wants to see you.’ I

go into Coach Stas’s office and sit down and he says, ‘Heyyy, Liiiiineberrrry, I got a reporter from the Raleigh

News & Observer

saying that we had an East Carolina football player in an anti-war

demonstration. I told him, we didn’t have East Carolina football players

in anti-war demonstrations’ – meaning, you’re gone if that is what you

were doing. I was like, ‘No coach, no. I was beating them up… I

was fighting them.’ So he says, ‘Ohhh… well that’s good Liiiiiineberrrry.

You go on and get your equipment and get out there to practice.’

In East Carolina’s first game against

Southern Mississippi,

in 1966,

Lineberry (left) and Neil Hughes (43) converge

on the ball carrier.

(Submitted)

He chuckles about the story now, but

Lineberry can’t really retell it without the laughter eventually

turning to pain.

“My brother came (from his first tour in

1966-67) and actually made it to East Carolina quite a bit,” Lineberry

said. “He went back in 1970 for his second tour there and was killed. He

was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross.”

In an ironic note, Jerry Lineberry was

attached to the 7th Marines of the 1st Marine

Division for his second tour and that very unit is the same that Wayne’s

younger son, Jerry Matthew Lineberry, served with in the Marine Corps.

“I named my youngest son after my brother,”

Lineberry said. “My brother was Jerry Eugene and my son is Jerry

Matthew. It is (ironic) that they both were in the same unit.”

Much like the fight in the Student Union,

Lineberry always identified with the toughest of times. Where many a

player might hope to draw the weakest link in an opponent to exploit,

Lineberry was very much the type of guy who wanted the toughest match

up, the biggest challenge. So it is no surprise that he recalls most

vividly some of the toughest moments he encountered as a player.

“In 1966, we played Louisville and Southern

Miss and they were playing like an SEC schedule then,” he recalled. “We

played West Texas State who had Mercury Morris and Duane Thomas – who

played little because of Abbie Owens – and there were five or six of

those guys who were with us with the Buffalo Bills. These were good

football players. But, have you ever heard of Parsons (Iowa) College?

Now get this and this is very important because people think you‘re

crazy if you retell it, but Parsons College was written about in

Sports Illustrated and was called “Flunk Out U” because anyone with

money could go there.

“Now they only lasted (as a program) about

two years before they went by the wayside. Then the University of Tampa

took over as far as the outlaw school, with guys like (John) Metuszak and

those guys and then that went by the wayside.”

Lineberry continues:

“Now Parsons dressed in Green and White

just like the New York Jets,” he said. “I played against the New York

Jets and Parsons College was bigger than the New York Jets. The fullback

was Frank Antonini, who was an all-SEC player at Kentucky, and then there

was a receiver who was all-SEC at Alabama who had to leave for some

reason. They were a semi-pro team. We were the only team that ever beat

Parsons at Parsons. We beat them 27-26 on a frozen field and it was

absolutely miserable. But it was a

Neal Hughes highlight film. He was

going on both offense and defense. So Hughes made a long run and scored.

“It was the most beautiful highlight I’ve

ever seen… he’s going down the sidelines with a safety. He and that

safety are juking each other for about 40 yards and Neal is going back

and forth with shoulder moves and the guy is following him and finally

the guy trips up and Neal goes into the end zone. We go ahead of Parsons

by one point. We kick off and the very first play, the guy runs around

the end and is gone for a TD. You can see Neal on the film coming from

the top of the screen… you see Neal Hughes come across the field at an

angle. The guy is running for like an 80-yard touchdown. Hughes runs him

down, grabs him at the back of his jersey and brings him down around the

3-yard line to save the game. It was just unbelievable.”

He gets excited when he talks about his

former teammate.

“We had guys like Neal – and I played

either with or against three Heisman Trophy winners (in college and in

the pros) –

and Neal was just as good as any of them, if not better. We had some

great players at East Carolina.”

Lineberry also likes to retell the story of

the hardest hit he ever witnessed.

“We went to Southern Illinois in 1966 in

Carbondale (IL) and they were a huge team, too,” he said. “It was a punt, and Flowe peeled back around and was coming down the sidelines and this big

old guard – I think Robert Ellis (WB, 1964-66) was running the ball to

the sideline – and this big old guard was reaching out just fixin’ to

tackle Billy. So this guy has run 20 or 30 yards and Flowe is running 20

or 30 yards – that’s a lot of mass coming together – and Flowe is coming

right at him and this guy never sees Flowe. Just as he’s reaching out to

tackle Ellis – right in front of our bench – Flowe went past him and the

only thing that hit him was Jim’s forearm to his face, so the guy goes

parallel and his helmet came off like someone threw it down the field

about 15 yards.

“The guy got up and fell down and kept

getting up and falling down but they got his helmet and his ear was in

his helmet. Now that is what I’m talking about hitting at East Carolina.

That was a good one. We always tried to hit as hard as we could, but I

don’t remember ever getting one off like that myself. We were just kind

of a mean team then.”

He gets excited thinking back on his years

and how he played as a Pirate.

“I will say one thing, there were a couple

of times, without being specific, but I could have intercepted a lot more

passes as a linebacker, but the best hit in the world is when a back or a

wide receiver is doing a down and in and they are stretching out for the

ball and you’re coming the other way and you just put your helmet in

their chest,” he said. “I mean right in their numbers and you try to

take one lung and put it over there with the other lung. That was always

fun to do.”

Toughness

Equals Opportunity

Coming off a tough 4-6 senior season,

Lineberry wasn’t sure of his future. He felt deep inside that being

played out of position on the defensive front most likely erased any

opportunities he might have on the next level. It was wartime and having

a brother who had spent a tour in Vietnam and living in a pro-war

atmosphere, Lineberry mulled following in his brother's footsteps as a post-graduation next

step.

“I thought about the Marine Corps,” he

recalled. “When they asked me what I majored in, I said, ‘Staying

eligible.’ But, I also always wanted to get to the NFL. The pro scouts

always came around and they talked to a bunch of us and they timed us. I

remember there were a bunch of scouts around. I was over 240 pounds and

they just had you take your helmet off and run in full equipment and I

was running 4.9 forties in full equipment. That wasn’t that bad for

those days. They would talk to you but you don’t know you were getting

drafted or not, so I was thinking about joining the Marines… I was

surprised I was drafted.”

The call came from the Buffalo Bills in the

17th round.

“When I got drafted, I was surprised,” he

said. “I was actually talking to the Marine Corps. You gotta understand,

in 1969, if you went to Vietnam as a 2nd Lieutenant, your life

expectancy was like 15 minutes. But, my name come up and I was drafted

(by the Bills). Now that was in the same class as O.J. Simpson and he

got all the money anyway. None was left over for the rest of us guys,

but I tagged along up there to play.”

Which was true, at least, in Lineberry’s

case. The throwback linebacker consulted his throwback coach and got

some advice that might have been pure, but not so wise.

“Well, you listen to your coaches and Stas

told me, and he meant well, he said, ‘Hey, don’t sign for a bonus, go up

there hungry,’” Lineberry recalls. “He wanted me to make the team. So,

(Buffalo) sent a little equipment by a guy and I signed the contract. I

get up there to Niagara University and they’ve got free agents up there

with thousands of dollars in the bank and I am like, ‘Hey what is

this?’ ”

Lineberry was quickly introduced to the NFL

in camp.

“I was having to play outside linebacker,”

he recalled of his first camp. “I remember, I got tied up with this big

old tight end and I had first back out of the backfield

(responsibility). He had a couple of steps on me – about five yards – it

was O.J. Simpson, and I was like, ‘I ain’t catching the Juice, you

know.’ ”

Indoctrinated to the talent level,

Lineberry settled in to make a run of it. And he did well and had a lot

of fun doing it.

“There were a lot of great guys there and

good camaraderie,” Lineberry described. “And talk about politically

incorrect guys... a lot of teasing and carrying on. I got cut and in

those days they had farm teams in the Atlantic Coast Football League and

Buffalo had the Hartford Knights. Well, Buffalo sent me down to Hartford

and I was the middle linebacker there in 1969. Then, I went back to

training camp in 1970 and made the final cut. But then I got cut two

weeks later on a business deal thing and I got sent back down to

Hartford and finished up with the Knights for two years at linebacker.”

After two seasons in the ACFL, Lineberry

felt like he saw the handwriting on the wall for his professional

career, so he made a change.

“I went back to graduate school at East

Carolina,” he said. “I didn’t know if I could go back to the Bills that

year, though I knew I could certainly go to Hartford to play. But, I

already had my teaching degree, so in 1971, I just went for my Masters.

“It was hard to leave football behind, but

I’ve always been a fan of East Carolina (where he returned for school).

I watch very little pro ball now. The first two years I got out of pro

ball, I didn’t want to watch it because (as you are developing) you see

the Dick Butkuses of the world killing people and every day they are

bigger, faster, stronger. You build it up so much in your mind by

watching it, but then you get out there (in the pros) and you get knocked

down and you say, ‘You know what, it wasn’t fatal.’ It’s like going from

the junior varsity to the varsity and it kind of busts your bubble about

pro football.”

Back in the Pirate Family

In ’71, Lineberry was a graduate assistant

under Sonny Randle. Among the players Lineberry found and recruited was

a 5-11 defensive end from Havelock named

Cary Godette, who turned out to

be an All-America at East Carolina. Lineberry had insisted that, though Godette was not the 6-3, 6-4 type most Division I colleges were looking

for, the defensive end would be a great one at East Carolina. Godette, of course,

proved him correct and he never forgot it.

A story that Lineberry likes to recall when

talking about the type of bonds forged as a Pirate:

“My son played football at Sabino High

School in Tucson, AZ – the same program that (current Pirates safety)

Zach Baker played for. Philip’s team in 1989 went 12-2 with a unique

group of guys. The next year they went 14-0 and won the 4A State

Championship. So, while Zach came out of the program talking about Sabino High School being a powerhouse, well, my son helped lay the

foundation for that. He was a linebacker and center and played defensive

line. He was All-State but was not a Blue Chip recruit. I put together a

highlight film of him and sent it to Cary Godette because I wanted

Philip to be a Pirate. Now, Philip was not 6-0 and Cary remembered that

other player who wasn’t quite 6-0. (Despite that) Philip went to Eastern

Arizona Junior College and then went on to play at Northern Arizona.

But, Cary never forgot. I saw Cary at the Letterman’s Weekend (2004) and

gave him a hug.”

It was these types of relationships that

had so bonded Lineberry to East Carolina, that it sometimes made making

the right career decision the hardest thing to do for a tried and true

Pirate.

“In 1972, I went home to Wadesboro,” he

said. “I was the head football and wrestling coach and did that for one

year,” he said. “At Wadesboro, we had a lot of rebuilding on the

football team, but I took the wrestling team and did real well with

that. You can turn a wrestling team around real quick. I enjoyed it. To

this day, I go to Wadesboro and I have guys come up to me and I’m their

coach and I only coached one year. I mean it really touches your heart

when you experience that.”

His coaching career at Wadesboro – and in

general for that matter – would be short-lived as another influential

Pirate came calling.

“Harold Bullard, one of our East Carolina

coaches, had gone with New York Life,” he explained. “A bunch of us

(former players) fell in with him. I went to the office in Charlotte in

1973 with New York Life and then in 1975 went through the Management

Chairs and I did that for most of my years (in the insurance business).”

So was the beginning of a stellar career in

the insurance business. It is fitting that it was one of his coaches who

mentored his non-football career. Where Bullard was a corporate sponsor

for Lineberry, it was Emory who was the biggest influence.

“Ed Emory was that kind of coach for me,”

Lineberry said. “I liked most of my coaches, but Ed had always been a

father to me. Actually, I was one of the ones pushing for his Hall of

Fame induction for years. He was very deserving. When he was out of

coaching before he went to Richmond (Senior) and he was in Wadesboro as

the Junior High principal, I would always get around Ed and I’d say, ‘I

was Ed’s first all-American and I made him everything he is.” And he’d

said, ‘Thanks a lot, that’s why I’m a principal.’ He is still one of my

best, dear friends today.”

Finding His Way Home

Lineberry has always followed the program

since he left Greenville following his playing days. He has been a loyal

Pirate Club member and he has been a fan, making his way to as many

games as he could each year. Everything was pulling him back to his

beginnings. And the pull has never been stronger than it has been of

late, watching his beloved program fall on hard times.

“In 1983, I was dropping thousands of dollars for

flights to get to the games,” he said. “And, I cannot imagine not going

to the games. When it is football season, you go to see the Pirates

play.”

He has oftentimes thought how gratifying it would

be to have a few minutes with some of the players on the team to share a

little of his own history.

“I think it comes back to – and I was talking to

Harold Robinson, and he was like, I could come talk to the team about what

it means to be a Pirate and about the chip on the shoulder – and I

thought about, ‘Why did I wind up a Pirate?’ When you have to fight for

everything you have, you get the Pirates’ attitude. You get the attitude

of Leo Jenkins – God Bless him – you get to be associated with him. He

has had such a great impact on many of us and we watched how he fought

the big boys in Chapel Hill and Raleigh.

“You get out there and it carries on throughout

life, what it means to be a Pirate. I have been honored and privileged

that since 1965 I was given the chance to be a Pirate. What is the

saying, ‘Pirate born and Pirate bred and when I die I’m Pirate

dead.' I always feel the same excitement when I come back, even during

the down times.”

And what else would he tell the current players?

“I would tell the players about what it means to be

a Pirate and what it means to be standing out there on your home field.

What those boys learn on the football field will last them for their

lifetime. I am still close friends with many of my teammates… they are

among my best friends.

“I would tell them that ECU is a bonding

(experience) that is unique. Everyone is in the same boat and sometimes

that boat may be in rough waters and leaking and you look over at the

people on the luxury liner like the wine and cheese crowd in Chapel

Hill. We all talk all the time – me, Jim Flowe and Battle Wall – I talk

to Battle, and UNC just doesn’t have the same chip on the shoulder. When

you make steel, you have to heat it up and pound the hell out of it. (UNC-CH

and N.C. State) just haven’t been through what we’ve been through and had to

fight for everything they got. I look back, I could have played anywhere

and I’ve thought about it over the years, ‘How did I end up at East

Carolina?’ But it is one of the greatest things in my life, it is one of

my life’s enjoyment.”

Lineberry’s ETA for Greenville is nearing, he

hopes, and perhaps he will get his chance to share his stories with the

current players. He wants to make money for the future of the

program… and he really doesn’t have too many other hobbies these days.

“I enjoy ECU football the most,” he said. “Of

course, I still work out and keep in shape. I proved that I don’t play

golf at the Lettermen’s golf tournament, because I borrowed Matt

Maloney’s clubs and after 18 holes, I said, ‘Matt this is terrible you

don’t have any good shots left in these clubs.’ When I was out West, I

learned to snow ski out there – you know with the Rocky Mountains and

Telluride right there.

“I played team tennis out there for nine years and

I played five or six times a week. I was a 4.0 (USTA rating) so we’d

play on Saturdays and practice and we were playing all the time. I was

frustrated because as a 4.0 player you can hit the ball back a few times

but if I couldn’t get to a 4.5 or a 5.0, well, I just walked away from

it. In 1992, I came back (to VA) because I am a Southern boy and I had

to fly all over the country to see my Pirates, but when I got back in

1992, I dropped my racket and never pick it up again. And this ties to

ECU football and my personality. To be a good tennis player, you have to

be able to think two, possibly three shots ahead and I could never do

that. I tried… I have tried, but all I can think about is that guy across

the net with skinny legs is beating me and I just want to jump across

the net and beat him to death with my racket. I’m dead serious. I’m

saying, ‘Go ahead and take some more lessons to get to a 4.5 or a 5.0 or

just give it up.’ I still have those rackets in the closet since 1992.”

Getting back home to Greenville for good might be

just what the doctored ordered for his psyche, but it could come at a

hefty price to his ticker if things don’t change soon with his beloved

Pirates.

“It’s always hard for me at the games,” he laughed.

“And I (have) to tell myself (sometimes), ‘Wayne they’re not paying you.

You’re not in school anymore, it ain’t my job anymore. That was 30 years

ago.’ When they don’t hit anybody out there, it drives me crazy.”

Lineberry is a fighter, in more ways than meets the

eye. He likes to tell another story about that fighting spirit.

“I see

Jim Gudger a lot when I’m down in

Greenville,” he said. “And this story is really his story, but I like to

tell it. We played at the University of Tennessee in 1996 and I hadn’t

seen Gudger in a long while and Jim said he was walking by a crowd

(tailgating) and saw a big commotion and he saw me right in the middle

of it. Now this was the first time he’s seen me in years. I’m standing

in a group of about 50 or 60 (Tennessee fans) and they were mouthing off

at East Carolina people and being rude – kind of like those fans up at

West Virginia this year (2004). I was like, ‘Come on all you SOBs,

c’mon, let’s go!’ I was challenging the whole group.

“So Gudger walks up and says, ‘Now you guys are in

trouble, there’s two of us.’ That was funny… here’s Gudger going

back-to-back with me in this crowd of Tennessee fans. Guess they thought

we were crazy and the left us alone.”

He is definitely a fighter and his spirit has never

been tested as much as it was recently when he faced much more than a

crowd of angry Vols fans.

“This past May, I went in for a physical and my PSA

was up,” he said. “I never had any problems like that in my family and

here I find out I had cancer. So a week later, I’m in the hospital and

I’m like, ‘Filet me like a fish and take it out! Do whatever you got to

do to kill it.’ They took it out and then the PSA went back up. This was

just a couple months ago. I took a shot, went through radiation even

though everything got cut out, but evidently some cells were in the

pelvic area. But I went to the doctor’s and had a blood test and it’s

gone. I had the Grim Reaper by the throat and I’m trying to kick his

butt. Of course, it wasn’t me, it was a higher power that did that

(defeated the cancer).”

Lineberry didn’t want to go into much more

detail… no need. He took it head on and he is, so far, winning that

grapple against the Reaper.

If the brush with mortality did anything in

Lineberry, it was to accelerate his plans for the future. And he is glad

that that future is going to start sooner rather than later.

Lineberry, 3rd from left standing,

tailgating in 2004

with friends, from left: Tracy and Lee Durham, Wayne,

fiancee Diane. (Submitted)

“I’ve been a Pirate Club member for 28 or 29

years,” he said. “I’ve been a community chairman and everything else.

I’ve been coming back with the same friends and have been since we got

out of school. It amazes me that more – especially athletes – don’t

give back. I’ve been since I was up in Richmond when I first went into

management with New York Life. Stuart Siegel and I started the Pirates

Club back up, up there (in Richmond). Just getting people to come out

and have some beer and get Ed Emory or Pat Dye to come up there, you

know. So I’ve been involved ever since I left school.

“Of course, Id like it if we were getting the BCS

money. Look at what Wake Forest and Duke get for their program. Wake’s

come up but I mean they get $7-8 million a year from their BCS cut. It’s

kind of like Pirates helping Pirates… we’ve got to put the money in the

bank. Nothing has ever come easy for us and that is why we have the chip

on our shoulder. We’ve got to put the money in the bank ourselves and if

its there, fine, we don’t have to worry about going to I-AA because we

put the money in the bank ourselves.”

Lineberry is excited now that his endowment

strategy is

rolling out with the Pirates Club. With his former teammate and head of

the Pirates Club, Dennis Young, working with him, he feels like his mark

will be deeper than the blood, sweat, and tears he left on the Ficklen

turf as a player. His legacy, he hopes, will be putting in place the

foundation for an endowment that is beyond the wildest dreams of those

who count themselves among the Pirate faithful.

“It’s like everything else we have faced (and

conquered) in the past,” he said. “We don’t know any other way (but to

succeed).”

Send an e-mail message to Ron Cherubini.

Click here to dig into Ron

Cherubini's Bonesville archives.

|